Hauntology of the Internet: Ghosts in the digital machine

There is a particular silence that lives beneath the noise of the internet.

A low-frequency hum of unfinished conversations, abandoned profiles, missing contexts, and memories that never fully die. We scroll through a landscape of the present that is always slightly out of sync with itself—a digital world haunted by its own past.

Philosopher Jacques Derrida coined the term hauntology to describe futures that never arrived and pasts that cannot be fully buried. On the internet, this condition is not theoretical. It is the architecture.

The digital world was never designed to forget. It accumulates traces of our lives the way old houses accumulate drafty corners, creaking floors, and unexplained noises. Nostalgia becomes code; memory becomes metadata. And we, the living, move through this ghost-dense environment often without noticing that we are not alone.

To speak of “ghosts in the machine” is not mere metaphor. It is an honest description of the uncanny presence that saturates digital life: the sense that something is here that should not be, or that something is missing that should be.

The internet is not simply haunted.

It is hauntological—a medium built from lost futures and persistent echoes.

The Internet as a Cemetery of the Almost-Recent

Every platform is a graveyard of versions of ourselves.

Old posts we forgot we wrote.

Photos of friendships that dissolved years ago.

Notifications from apps that no longer exist.

Music we loved in adolescence but haven’t revisited in a decade.

We wander through these artifacts the way one might walk through an old neighborhood—recognizing landmarks yet feeling estranged from the version of the self who inhabited them.

Unlike physical memory, digital memory does not fade. It lingers. It hovers in a perpetual present, re-emerging in algorithmic “on this day” reminders or resurfacing through a search result. In that sense, the internet is not just a repository of content; it is a storage of ghosts—identities we outgrew but never buried.

This creates a strange temporal condition: we are constantly confronting our own past selves as if they were still alive. Online, the past refuses to stay past.

And in this refusal lies the first ghost of the digital age:

the self we once were.

Lost Futures and the Broken Timeline

If the internet was once utopian, it is now decidedly haunted by that lost promise.

In the 1990s, it carried the dream of radical freedom—a decentralized commons where creativity would flourish and democracy would deepen. In the 2000s, social media arrived with promises of connection, transparency, and global understanding.

What we got instead was a world where platforms harvested attention, algorithms manipulated perception, and surveillance capitalism devoured the idealism that built the early web.

We are haunted by these broken futures.

We scroll through feeds designed not for community but for manipulation. We witness platforms cannibalize themselves. We remember the early internet as a frontier of possibility and feel, even if we cannot articulate it, that something has been lost.

This is the second ghost:

the internet we were promised but never received.

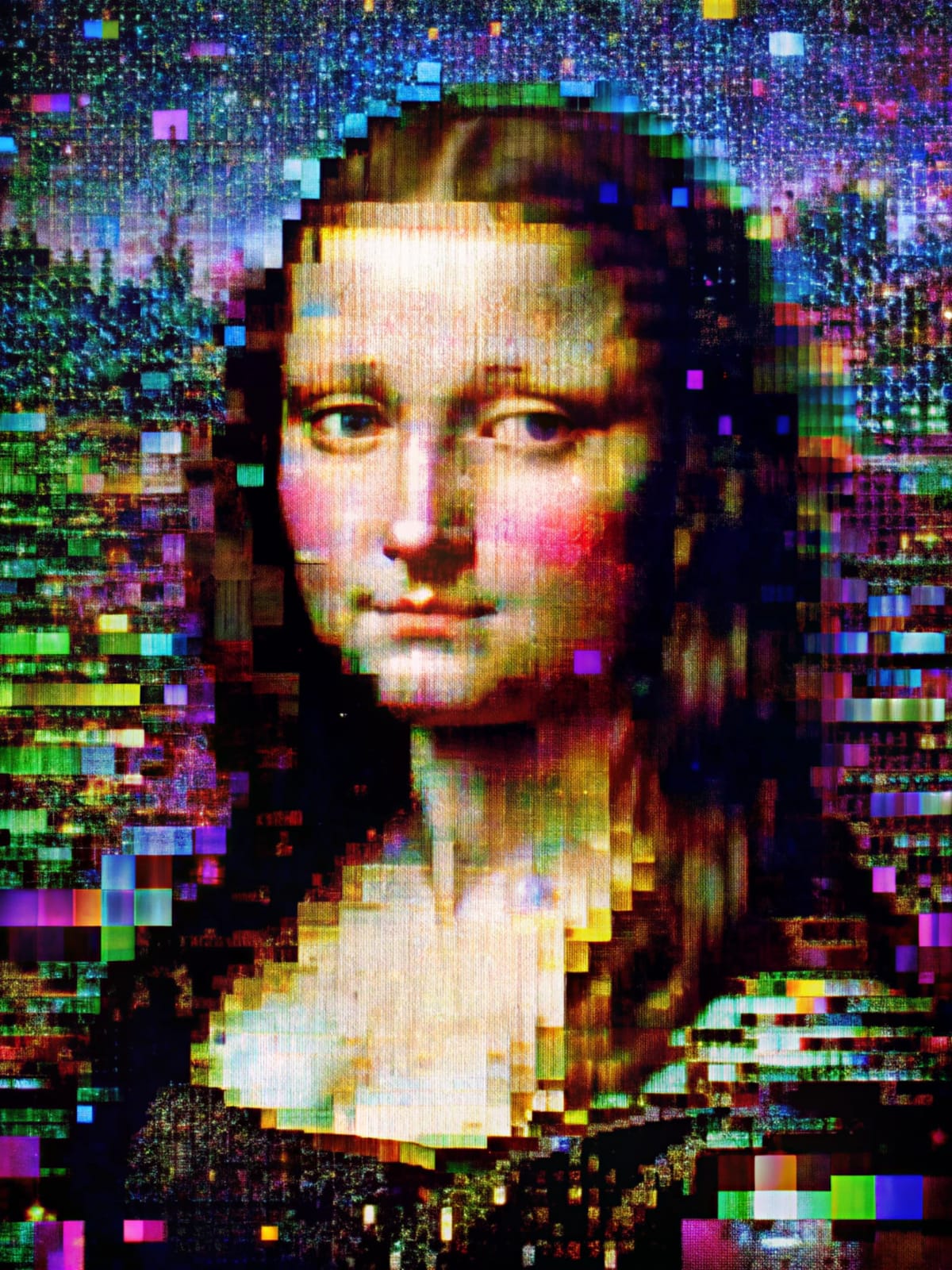

Hauntology teaches that ghosts appear when time malfunctions—when the future becomes stuck, looping back to its own past. The internet today feels like exactly that: a technological present looping endlessly through nostalgia, memes, remixes, and recycled aesthetics because it has lost its sense of direction.

We live in a temporal glitch.

The digital present is an echo chamber of yesterday’s dreams.

Digital Echoes and Algorithmic Hauntings

Algorithms are mediums in the literal sense: intermediaries between us and the infinite archive. They shape what we see, what we remember, and what we forget. But in doing so, they also create echoes—patterns of content rising from past behavior to haunt the present.

You watch one video about astronomy, and for weeks, the ghost of that interest follows you across platforms. You buy a gift for a friend’s newborn, and suddenly you’re haunted by ads for parenting guides.

The machine builds a version of you that persists long after your interests change.

This spectral “algorithmic self” shadows your real one.

We are haunted not only by who we were, but by who the machine believes we still are.

In this sense, algorithms perform a kind of low-grade necromancy. They resurrect fragments of our past behavior and treat them as living truth. They mistake echoes for intentions. And we, in turn, are forced to navigate a world where our digital ghosts are often louder than our living selves.

The third ghost of the internet is therefore:

the algorithmic double—our predictive apparition.

The Architecture of the Unfinished

The internet is also crowded with ghosts of the incomplete.

Unfinished projects.

Abandoned blogs.

Half-written drafts in the cloud.

Defunct websites preserved by the Wayback Machine like digital ruins.

A strange melancholy lives in these partial architectures. They remind us that online life is full of beginnings without endings—initiatives abandoned, communities dissolved, platforms shuttered. In physical life, endings have rituals: funerals, goodbyes, closures. In digital life, things simply vanish or drift into silence.

Every online disappearance generates a spectral trace.

A username that stops posting.

A friend who goes offline without explanation.

A creator whose archive remains long after they have died.

This creates a fourth ghost:

digital disappearance—absence without closure.

It is no accident that younger generations use the word ghosting to describe relationships severed without explanation. The internet has normalized forms of vanishing that leave traces rather than endings.

We live with too many openings and too few conclusions.

In such a world, haunting becomes inevitable.

Collective Ghosts: Myths, Memes, and Shared Echoes

There is another kind of ghost in the digital machine: the collective archetype.

Memes, trends, viral aesthetics—each one is a kind of cultural hauntology, a specter of shared meaning that rises, spreads, decays, and sometimes reappears years later.

A meme is not an idea.

It is a ghost—an echo without a speaker.

And like all ghosts, its power lies not in its origin but in its transmissibility.

These collective ghosts shape perception in the same way oral myths once did, but with less grounding and more volatility. They flicker, mutate, haunt for a while, and then vanish. Until one day they return—altered, distorted, or ironically revived.

The internet is a haunted house of cyclical culture, where nothing ever fully dies and nothing fully resolves.

Why We Are the Ones Who Haunt

The deeper question is not what ghosts haunt the internet, but:

Why does the internet feel haunted at all?

The answer is uncomfortable:

Because the internet did not become haunted—we did.

We brought our unresolved griefs, our unfinished stories, our unspoken longings. We built systems that preserve everything but fail to give it meaning. We created tools that archive without honoring, remember without understanding, and replicate without reflection.

Hauntology is a symptom of a society that has lost a coherent sense of time—trapped between nostalgia for a past that feels more real and anxiety about a future that feels increasingly unreal.

The digital landscape amplifies that condition.

It is not haunted because it contains ghosts.

It is haunted because it contains us, multiplied and fragmented, reflected in infinite permutations.

The final ghost, then, is the most unsettling:

we haunt ourselves.

Toward a More Conscious Digital Presence

If the internet is haunted, the question becomes:

How do we live with our ghosts?

Not by exorcising them.

But by listening.

A hauntological approach to digital life asks us to:

• Acknowledge the unfinished nature of our online selves

• Recognize the emotional residue of digital memory

• Create rituals of closure for digital departures

• Reclaim the future from the looping nostalgia of algorithms

• Practice conscious presence in a space designed for drift

The internet may never be free of ghosts.

But perhaps that is not the goal.

Perhaps the task is to become better stewards of the digital spirits we’ve created—our past selves, our lost futures, our algorithmic doubles, our collective echoes.

To inhabit the internet with attention is to walk through a haunted house with the lights on—not to banish the ghosts, but to understand what they are trying to tell us.

Because in the end, hauntology is not about fear.

It is about recognition.

The ghosts in the digital machine are reminders of the lives we have lived, the possibilities we have lost, and the futures we still have the power to imagine.

And if we listen closely, the haunting becomes a guide.