The Ideas That Academia Rejected (and Why They Matter)

Profiles of thinkers who left—or were pushed out of—the institution.

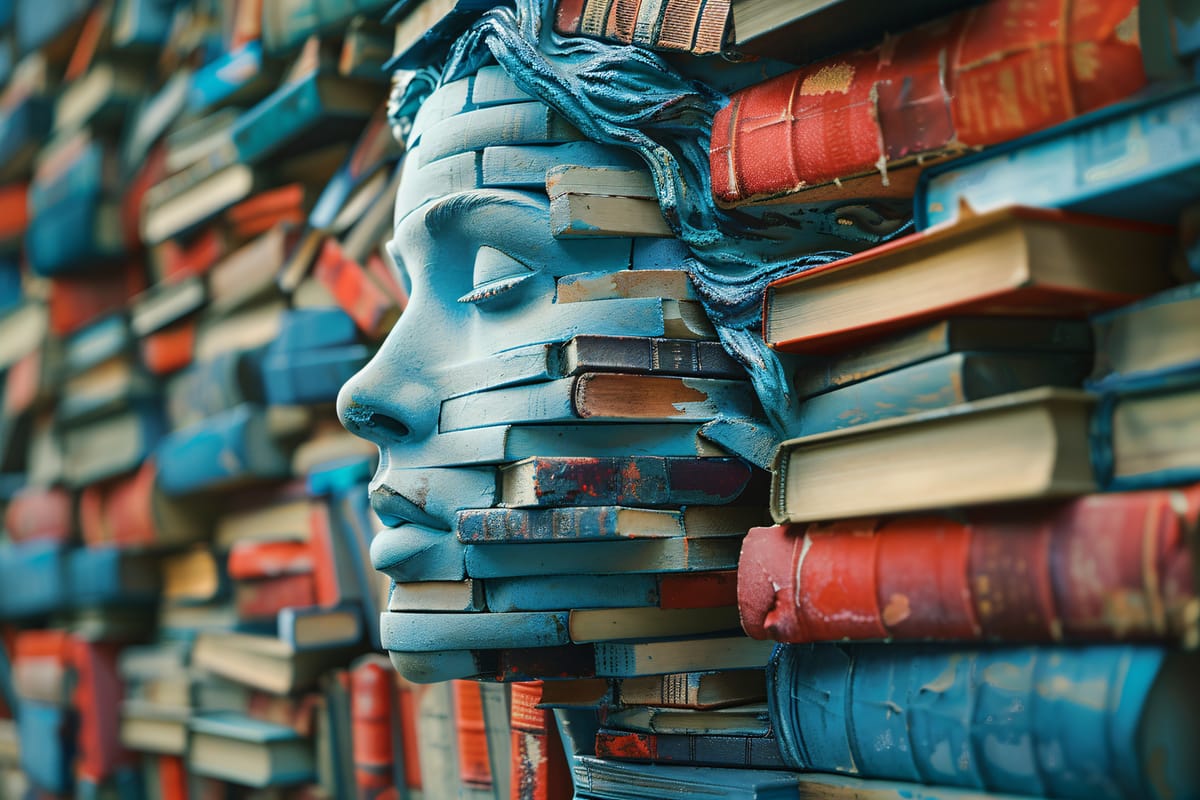

Academia was once imagined as a sanctuary for thought—a place where ideas, however controversial or complex, could be explored freely, tested rigorously, and debated in good faith. But over time, the institution became a system. And like all systems, it developed boundaries: social, ideological, epistemological.

Today, the university remains a center of learning. But it is also a gatekeeping apparatus—a structure of incentives, politics, and unspoken norms that determines which ideas rise, which are ignored, and which are quietly exiled.

This essay is about those ideas—and the thinkers who carried them.

Some left by choice. Others were pushed. But all of them inhabited forms of intelligence too unruly, too integrative, too symbolically strange—or simply too inconvenient—for the institutions that claimed to steward knowledge.

These are not stories of victimhood. They are stories of intellectual sovereignty—of thinkers who refused to contort their work to fit narrow expectations. And they matter now more than ever. Not because they were “right,” but because they show us what gets lost when knowledge is constrained by credentialism, ideology, or scalability.

Why Ideas Get Exiled

Before we meet the thinkers themselves, let’s name the patterns. Why does academia reject certain ideas or frameworks?

The reasons are rarely explicit. It’s not usually a matter of censorship. More often, it’s a function of institutional drift—the slow, subtle movement of norms toward safety, clarity, and careerism.

1. Epistemic Nonconformity

Ideas that challenge the underlying assumptions of a discipline—its methods, categories, or scope—are often dismissed as “unscientific,” “unrigorous,” or “anecdotal.”

2. Interdisciplinary Drift

Many institutions claim to value cross-disciplinary thinking, but in practice, hybrid frameworks often lack a home. The more a thinker blends modes—philosophy, psychology, myth, art—the less legible they become to any one department.

3. Symbolic, Spiritual, or Intuitive Knowing

Work that centers intuition, mysticism, or symbolic literacy is often rejected outright—not on its merits, but because it defies the norms of propositional logic and peer-reviewed positivism.

4. Emotional Honesty

Academic culture often rewards detachment. Work that brings emotion, vulnerability, or subjectivity into frame is seen as suspect—even when rigorously argued.

5. Political Inconvenience

Some thinkers are rejected not for their style or method, but for the threat they pose to institutional narratives. Their ideas are too destabilizing—morally, historically, or economically.

In all cases, what is rejected is not just content—it is a way of perceiving. And that loss is not just intellectual. It is cultural, ethical, and spiritual.

Profiles in Exile

Let’s meet some of the thinkers whose ideas were rejected—but whose work continues to resonate in the undercurrents of contemporary thought.

1. Ivan Illich (1926–2002)

Exiled from: Harvard, the Catholic Church, mainstream development theory

Why: Radical critiques of education, medicine, development, and institutional logic itself

Illich was an institutional insider who became one of its fiercest critics. His seminal work Deschooling Society (1971) argued that compulsory education systems do more to shape obedient consumers and citizens than to cultivate true learning. In Medical Nemesis, he exposed how modern healthcare often harms more than it heals.

Illich didn’t just critique institutions—he critiqued the modern idea of progress itself. He proposed that beyond a certain threshold, professionalized services create dependence, disempower individuals, and erode traditional forms of knowledge.

His work was dismissed as romantic, Luddite, even dangerous. But today, with rising distrust in schools, medicine, and development institutions, Illich reads less like a radical and more like a prophet of post-institutional consciousness.

2. Mary Midgley (1919–2018)

Exiled from: Mainstream Anglo-American philosophy

Why: Refused the split between science and ethics; challenged reductionist materialism

Midgley entered academic philosophy in the mid-20th century, when the field was dominated by logical positivism and analytic rigor. She refused to play the game.

Her work focused on the moral and mythic dimensions of science, especially evolutionary theory. She challenged the dehumanizing metaphors of “selfish genes” and critiqued the false dichotomy between science and religion. For this, she was often sidelined as “not a real philosopher.”

But Midgley anticipated many contemporary concerns: ecological thinking, moral psychology, and the symbolic role of narrative in scientific discourse. She held the line for philosophy as meaning-making, not just logic-chopping.

Her exile wasn’t loud. It was cultural. She simply didn’t fit the format.

3. Rupert Sheldrake (b. 1942)

Exiled from: Academic biology

Why: Proposed the theory of “morphic resonance”—non-local, non-genetic fields of memory in nature

A biologist trained at Cambridge and Harvard, Sheldrake was once a rising star. But when he published A New Science of Life (1981), everything changed.

The book proposed that biological forms are shaped by invisible fields of information, which act as collective memory. This idea challenged the materialist foundations of biology and sparked fierce backlash. Nature magazine called the book “a candidate for burning.”

Sheldrake’s work was dismissed as pseudoscience, despite his credentials. His exile reveals how scientific orthodoxy polices its boundaries, not only through evidence, but through aesthetic and philosophical discomfort.

Today, his ideas remain controversial—but increasingly relevant in fields like epigenetics, quantum biology, and consciousness studies.

4. Sylvia Wynter (b. 1928)

Exiled from: Mainstream philosophy and cultural theory

Why: Interdisciplinary work challenging the construction of the “human” in Western thought

A Jamaican novelist, dramatist, and cultural theorist, Wynter is one of the most important intellectual figures you've likely never been taught.

Her work critiques the foundational assumptions of Western humanism, arguing that the “Man” at the center of modern thought is a racialized, colonial, and exclusionary figure. She calls for a new understanding of the human—one that is hybrid, embodied, cosmopoetic.

Wynter's work blends philosophy, science, literature, and critical race theory—making it hard to classify and easy to marginalize.

But her refusal to fit academic boxes is exactly what makes her essential. She speaks from the threshold, and it is from there that she sees most clearly.

5. James Hillman (1926–2011)

Exiled from: Mainstream psychology

Why: Rejected the medical model of psyche; revived myth, image, and soul as psychological categories

Hillman, a former director of the Jung Institute in Zurich, eventually left institutional psychology to develop what he called archetypal psychology.

He rejected the idea that psychology should be modeled on medicine or biology. Instead, he insisted that the psyche is poetic, imaginal, and plural—not a machine to be fixed, but a soul to be engaged.

Hillman’s work was ignored or mocked by mainstream clinicians. But he gave voice to a countercurrent of depth psychology that saw the human being not as a case to be solved, but as a story to be told.

Today, as mental health discourse becomes increasingly medicalized and commodified, Hillman’s vision offers a symbolic re-enchantment of psyche.

Why These Thinkers Matter Now

Each of these thinkers was cast out not because they lacked intelligence, but because they challenged the unspoken frameworks of acceptability. Their work asked deeper questions:

- What counts as knowledge?

- Who gets to speak it?

- What kinds of perception are legitimate?

- What happens when we center complexity, ambiguity, myth, and soul?

In our current cultural moment—characterized by collapse, complexity, and epistemic fatigue—these questions are no longer academic. They are existential.

We are realizing that our dominant frameworks—materialism, technocracy, bureaucratic rationality—cannot hold the full range of human experience. We need intellectual refugees who saw the cracks early. Who kept thinking even when no institution rewarded them for it.

Their exile is now their relevance.

Conclusion: Building Outside the Walls

This is not a call to burn down the university. It is a call to build parallel epistemologies—spaces where thought can be strange, symbolic, interdisciplinary, embodied, and spiritually literate.

It is a call to honor the thinkers who were cast out not because they were wrong—but because they were too whole for the systems designed to manage fragmented knowledge.

And it is a reminder that the most important ideas of our time may not come from inside the academy, the algorithm, or the institution.

They may come from the underground. From the symbolic edge.

From the mythic, the exiled, the not-quite-credible.

And from those who never stopped asking the kinds of questions that don’t get funded—but might just help us remember how to think with soul again.